Max Bill Exhibition Museu De Arte De Sao Paulo in 1950

Article

A Bauhaus Domesticated in São Paulo

- EN

On ten March 1950, Pietro Maria Bardi, director of the São Paulo Art Museum (MASP, which opened in October 1947), signed letters addressed to several American educational institutions. His purpose in writing was to request the curricula of these schools as an help to developing the start design course in Brazil—the Institute of Contemporary Art (IAC), which, slated to open the following year, was to be run as a part of the museum and would also exist the country's first blueprint school. Despite being brief and objective, his missives did not neglect to mention the "spirit of the Bauhaus," explicitly linking the constitute he hoped to institute with a pedagogical lineage whose objectives and approach he aimed to share:

An Plant of Gimmicky Art has been founded past this Museum especially to teach architecture and industrial pattern such every bit pottery, glass, graphic art, iron, work, weaving, photography, piece of furniture, mosaics, plastics in general.

Artists and well known architects accept been invited to teach in the School; Max Bill, Piccinato, Nervi, Ruchti and others take already accepted the invitation.

We would similar very much to cheque our activities with yours which, since along fourth dimension nosotros highly appreciate.

We should like to attain something similar to what you are doing, always into the spirit of the Bauhaus. Therefore we should remain most grateful to you if y'all could transport us some publication referring to the curriculum of your University of Art.

Looking frontward to hearing from you we remain at your full disposition for whatsoever information and we give thanks you in advance.Believe us very sincerely yours.

P. M. Bardi – manager1

Letters were sent to the board of directors of the Cranbrook Academy of Fine art equally well as to Blackness Mountain College, where Josef and Anni Albers taught. Not only was at that place an explicit reference to the Bauhaus, merely also the intention, as noted in Bardi's letter, to invite the artist Max Bill to teach at the schoolhouse.

An Italian art critic and merchant based in Brazil since 1946, Bardi had been entrusted by the Brazilian communications magnate Francisco de Assis Chateaubriand with the chore of forming an art museum in the city of São Paulo soon subsequently his arrival. The city had modernized rapidly in the years after the Second World State of war and, with the foundation of the International Biennial in 1951, immediately became an international hub of the arts. Bardi was non only the managing director of MASP. Together with his wife, the Italian builder Lina Bo Bardi, he edited Habitat, a magazine dedicated to architecture, the arts and design. The IAC opened on one March 1951, the aforementioned appointment that Max Bill, former Bäuhausler and future manager of the Hochschule für Gestaltung in Ulm, opened an exhibition of his work at MASP.

Bardi's appetite to reference Bauhaus methodologies in his new schoolhouse was corking and sustained. The archaic Europe he had abandoned was in the process of reconstruction; the continent' population was still healing from the wounds suffered during the Second World State of war. In the postwar flow, South America, and Brazil in particular, had emerged as a force of renewal that, unburdened by the weight of the antiquarian past, expressed its ambitions through a period of steady industrialization, an outcome of the import substitution policies the war had made necessary.

Bardi's task in the years after the state of war had been to take advantage of depression prices on the world art market2 in order to build up a collection at MASP that would rival any First World fine art museum.3 At the same time, by juxtaposing works from the remote past with items from contemporary industry, MASP launched itself as an institution of an entirely new graphic symbol. The Museum showed graphic design and industrial objects, such as, for example, Thonet chairs, including them within this artistic set—a concatenation reverberating, ane might say, with Bauhaus teachings. Moreover, given the famine of educated design professionals to piece of work in São Paulo's burgeoning industries, founding a school of industrial pattern was an absolute necessity. This was likewise a reason, as Bardi wrote in numerous texts, why the school would continue the historic mission of the Bauhaus.

However, if in the letters sent to American schools Bardi fabricated mention of a generic Bauhaus, in other texts Bardi referred explicitly to the Dessau Bauhaus—specifically, the period directed by Walter Gropius. This reference is key to how Bardi envisioned the IAC: he never mentioned Weimar or Hannes Meyer, nor Mies van der Rohe and the short-lived Berlin Bauhaus:

The famous "Bauhaus" was built-in with Gropius, Breuer and others, the school of industrial blueprint creating numerous new solutions familiar to the states today similar steel-tube chairs, steel furniture, etc. Then the Americans continued and developed this experience at the well-known Institute of Design in Chicago, headed by Moholy-Nagy, former Bauhaus professor … All these initiatives cannot be ignored in Brazil, specially in São Paulo, a large industrial center. Today fine art can no longer exist seen as a specialty of a closed grouping. It has to meet this transformation of the face of the world made by industry and in the aforementioned proportions.4

Or in this excerpt from a newspaper article published in Diário de São Paulo, one of the city's main newspapers:

The Establish has a plan that has not been tried past any of our artistic organizations upward to now—it repeats in proportions that must of course be kept, the didactic plan formulated by Walter Gropius and his squad in the largest art school that Deutschland has produced in this century: the Bauhaus of Dessau.5

Ane tin can also read an explanation of the Bauhaus and the Plant of Design in Chicago, written by one of the most important teachers of the IAC, Swiss builder Jacob Ruchti:

The I.A.C. form in São Paulo is an adaptation to our weather condition and possibilities of the famous grade of the Establish of Design in Chicago, directed by the architect Serge Chermayett (sic), and founded in 1937 by Walter Gropius and Moholy-Nagy every bit a continuation of the famous Bauhaus of Dessau. … The I.A.C. therefore represents in São Paulo—in an indirect fashion—the main ideas of the Bauhaus, after its contact with the Northward American industrial system.half dozen

There is also an affinity between Pietro Maria Bardi's pick and that of the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in its presentation (exhibitions, publications, etc.) on the Bauhaus Dessau and Gropius. The community of artists and artisans created in Weimar was out of the question for a school that had set out to construct a vision of design São Paulo industrialists might emulate, for whom "artisans" were upholsterers, reproducing historicist styles in their manual and decorative work for the city'southward elite.

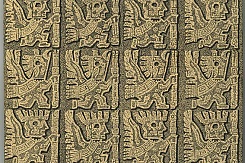

At the same fourth dimension, from early in its history some IAC teachers looked to the material and symbolic product of Brazil's rural peasantry, urban poor and Indigenous populations, in some cases appropriating elements of the handicraft produced past these groups in the design of certain objects.

A like concern was evinced in the thematic exhibitions of quotidian objects organized at MASP (one of the first didactic exhibitions of the museum had to do with the history of the chair), with objects consecrated past the history of art used to validate a de-hierarchization of cultural production. This conception probably derives, among other sources, from the theories of the art historian Alois Riegl, an of import reference for the starting time Bauhaus, who inherited his influence from Henry van de Velde, founder of the school's predecessor, the M-Ducal Schoolhouse of Arts and Crafts: for Gropius, for Pietro Maria Bardi and Lina Bo, also as for the Italian intellectuals who gathered around MASP, Riegl remained a key thinker. The intention to flatten the bureaucracy between the major and small-scale arts, likewise as Riegl'due south appreciation of the decorative artsseven and the decoration practices produced in the various crafts media, are included in the concept of Kunstwollen (a term first introduced in the mid-nineteenth century by the German language archaeologist Heinrich Brunn to describe the characteristics and boundaries of aesthetic design in a given epoch), assuasive one to see deep traces of universality in everyday objects. This line of thinking opened upwards a space for the symmetrical coexistence of so-called cult art and popular productions, creating affinities and overlaps betwixt the cultured arts and practices of craftsmanship. A foundational thought for the Bauhaus in its first phase in Weimar, Kunstwollen also strongly informed the concepts of Pietro Bardi, Lina Bo as well as a number of intellectuals and teachers associated with the IAC.

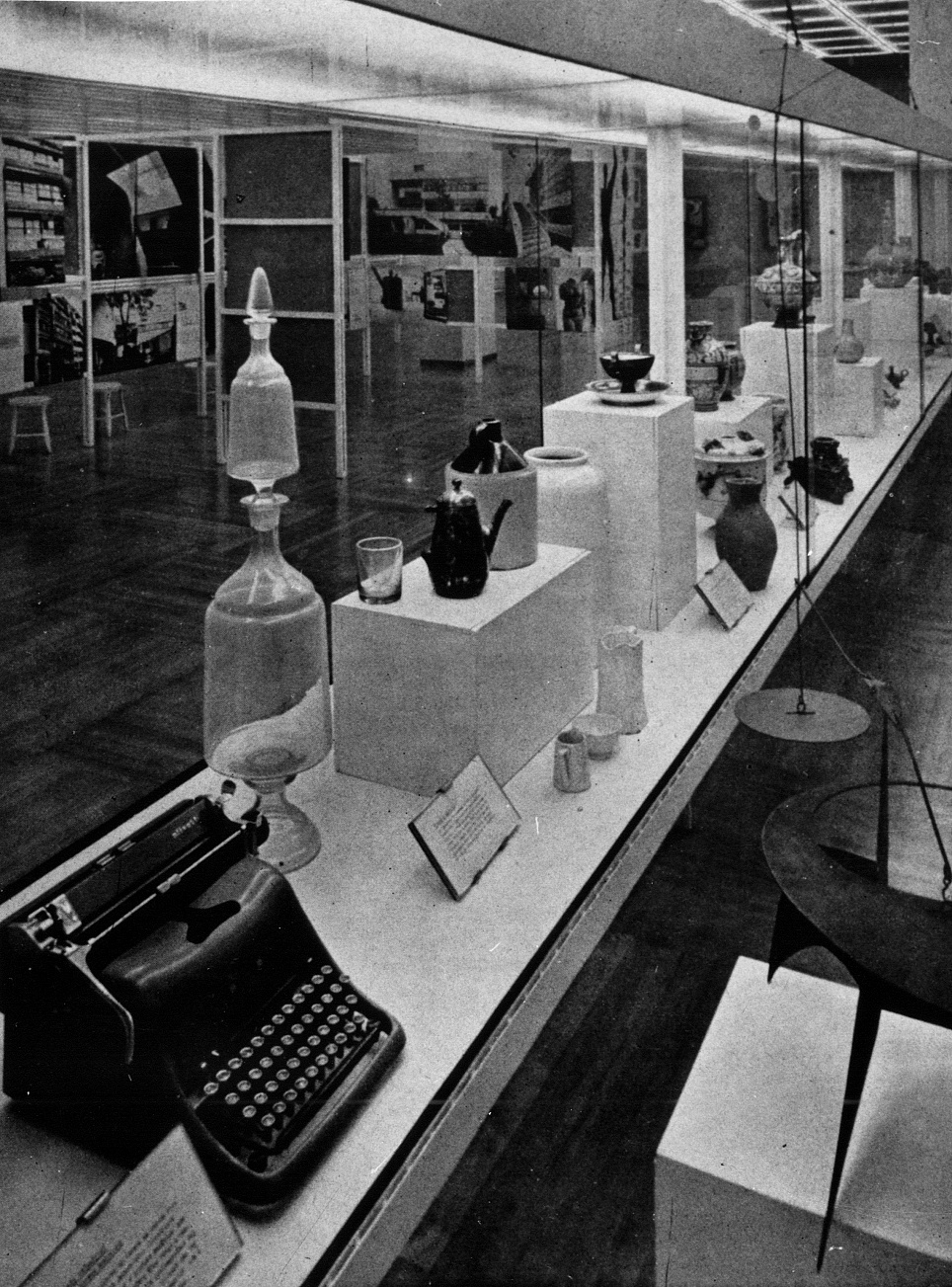

Exhibition view of Vitrine das Formas with typewriter Olivetti.

MASP Research Center / Instituto Moreira Salles / photograph: Peter Scheier.

This view of art reached new heights not but due to the Bauhaus but as well cheers to Le Corbusier, who although harshly critical of decoration and the decorative arts, brought artisanal and industrial production closer to an expressive synthesis.8 Bardi had possessed an affinity for Le Corbusier's thinking since the time of the fourth CIAM convention, which produced the Athens Lease.9

The propinquity between brainy fine art and art closer to and so-chosen colloquial culture appears clear on posters produced for MASP, especially those designed past Roberto Sambonet, an Italian painter and professor of drawing at the IAC, who designed graphics both for the museum and the school.10

The endeavor to elucidate this theoretical connection through MASP exhibition strategies is as well clear from the juxtaposition of technical objects, quotidian objects of the contemporary moment and commonsensical objects, such as ceramics and glassware dating from centuries past. Such was the conception of the exhibition Vitrine das Formas (literally "showcase of forms") mounted at MASP, which included the Olivetti typewriter designed by Marcello Nizzoli and a Brazilian copy of the Vigorelli sewing machine displayed next to historical objects. The strategy was so innovative for São Paulo's provincial environment that one of the city'southward leading newspapers of the time commented that the director had "forgotten" a typewriter in the shop window.11

Pietro Bardi explained the exhibition this way:

They are displayed in this display example from the curious root of a tree to the last type of Olivetti typewriter, passing through vases that are Egyptian, Greek, Florentine, etc. The typewriter is a typical instance of the artful possibilities of an industrial product, which was properly designed by an industrial designer.12

It can also be unequivocally stated that the IAC was in line with the practices of the Institute of Design in Chicago, which was led until 1947 past erstwhile Bäuhausler Lazlo Moholy-Nagy. The Chicago Institute and the North American industrial manner of production itself were likewise of import models. In several writings by Pietro Maria Bardi, it is as if the IAC and the school founded by Moholy-Nagy in North America shared the same conceptual cradle. Similarly, we can come across how Lina Bo's own do equally a designer resonated with the Due north American Bauhaus school—for instance in her piece of furniture designs made from cut-out plywood. Like industrial design itself, the notion of serial reproduction was inherent in Lina Bo'south furniture pattern from this flow.

The approximation of the IAC'south pedagogical contents with the Bauhaus, a connection well established by Adele Nelson,xiii is unequivocally evident in the workbook prepared by the aforementioned Jacob Ruchti, who taught composition at the school. Information technology contains, amongst other things, the teachings of Wassily Kandinsky, based on his book, Point and Line to Plane.14

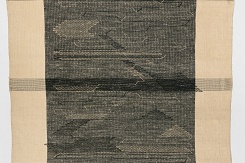

However, information technology would exist a mistake to believe that the IAC was a faithful re-create of the Bauhaus Dessau or the Chicago Plant of Design, for Bardi'due south appreciation of the Italian Futurists instilled a degree of originality in the Brazilian school. For instance, fashion was emphasized in the IAC curriculum, expressed not but through the products of the weaving workshop and printing classes—which created designs for womenswear, fabrics produced on mitt looms and printed fabric created by teachers and students—but also in parades organized by the museum, such as the celebration of haute couture demonstrated by the museum's hosting of a parade of Christian Dior fashion.

Pietro Bardi's admiration for the Futurists likewise explains his appreciation for Raymond Loewy, the French-born American designer fought by Bäuhauslers in the Usa.15 Loewy opened an office in São Paulo in 1948, taking on as an amateur one of the IAC's first students, Alexandre Wollner, who would later study in Ulm—an internship arranged thanks to Bardi's intervention.

Nathan Bernard Lerner and Hin Bredendieck, Plywood chair, ca. 1949. Milwaukee Art Museum, Purchase with funds from the Demmer Charitable Trust M2015.10, photo: John R. Glembin.

Lina Bo Bardi, plywood chair, Palma – Art and Architecture Studio, undated. © Instituto Bardi / Casa de Vidro, photograph: Peter Scheier.

From left to right: Pietro Maria Bardi, Dior's models, Lina Bo Bardi and Mr. Paulo Franco, 1951.

Photo: Unknown – MASP Research Centre.

The IAC was an amalgamation of theoretical matrices, resulting in a schoolhouse of nifty originality, and which, despite Bardi'due south eclecticism, not simply took its pedagogical model from the Bauhaus but also a means of cultural legitimation. Understanding the importance of this lineage, the school'southward founder did everything he could to establish links between the Bauhaus and the IAC. He published a text where he erroneously stated that the painter Lasar Segall (president of the schoolhouse congregation) was a Bäuhausler, when he simply visited the school and maintained a correspondence with Kandinsky.16 Bardi also similarly claimed that IAC weaving teacher Klara Hartok had been a educatee of Anni Albers at the Bauhaus.17 However, this kind of foundation myth-making does not invalidate the piece of work done at the schoolhouse, which, in fact, was in dialogue with both cultured, European forms of production at the same fourth dimension as it embraced the diverse production techniques particular to Brazil—whether these were divers, equally Lina Bo would term them years later, as "pre-artisanship" or as exemplary of the ornamental strategies used by Brazil'due south indigenous populations.

If there was a kind of cult to industrial methods and forms—equally evidenced by the museum's permanent display furniture based on aluminum tube supports, designed by Lina Bo Bardi—the school's curriculum as well clearly departed from those used at the Bauhaus and HfG Ulm. History was taught in the IAC, while at the Bauhaus (and at Ulm) history did not affair.18 And here, the weight of Italian instruction and, to a higher place all, an astonishing lack of education in the areas of art and architectural history in Brazil were stiff incentives for introducing these within the IAC curriculum.

Left: Wearing apparel by Roberto and Luisa Sambonet with experimental fabric based on basketry, cotton and raffia patterns, keeping the tradition of minimal decoration, which Anni Albers also followed, in the configuration of the structural threads of weft and warp, 1952.

Photo: Unknown – MASP Research Middle

Correct: Roberto and Luisa Sambonet, A women's garment based on Mondrian—well before a similar dress was designed by Yves Saint-Laurent.

MASP Research Middle / Instituto Moreira Salles / photo: Peter Scheier.

In my opinion, the IAC as a design schoolhouse tried to merge some practices and concepts, but this effort was premised on mistaken data. Pietro Bardi, Lina Bo and Jacob Ruchti started from mechanical reasoning, maybe wishing to transpose to Brazil the Italian postwar reality, in which pocket-size-scale industries successfully gained a asymmetric share of the international market through superior design.19 They understood that São Paulo, as an industrial metropolis where companies merely copied foreign models, needed designers and it would be upwardly to the school to railroad train these new professionals. Merely the companies of this catamenia were not at all interested in what the young people of the Constitute could offer. But copying European and/or North American standards was what São Paulo industrialists of the fourth dimension desired.

The Bauhaus of the Törten housing complex, and of practices based on a democratizing vision of bringing intellectuals and artisans together, was far removed from what the São Paulo elite wanted. Bardi, on the other hand, upheld the banner for a certain cultural updating of the industrials themselves. At no point in his soapbox almost the IAC was at that place any reference to the utopian grapheme of blueprint or its democratizing role—a standard that was held aloft past the leaders of the Ulm school and affirmed past Moholy-Nagy in Chicago.

If the dissimilar iterations of the Bauhaus, despite their curt duration, are still discussed to this day, with their multiple facets revisited by numerous researchers, the Bauhaus phenomenon in Brazil remains piffling studied. Certainly the Establish of Gimmicky Art at MASP is one of these disputed historiographical sites in which certain conceptions of the Bauhaus were presented and reformulated. This has allowed for very wide readings of the appropriations of the German school in peripheral parts of the globe, far from its European origin.

Common Threads — Approaches to Paul Klee's Carpet of 1927

_crop.jpg?w=245&h=163&c=1)

Jun. 10 2018

Paul Klees bildnerische Webarchitekturen

Apr. 8 2019

Weltkunstbücher der 1920er-Jahre — Zur Ambivalenz eines publizistischen Aufbruchs

Sep. thirteen 2019

Dry Time — Anni Albers Weaving the Threads of the Past

Apr. two 2020

Working From Where Nosotros Are — Anni Albers' and Alex Reed's Jewelry Collection

Dec. 11 2018

Andean Weaving and the Appropriation of the Ancient By in Mod Fiber Art

Jun. viii 2018

Anni Albers and Aboriginal American Textiles

Jun. 7 2018

Josef Albers and the Pre-Columbian Artisan

Feb. three 2020

"Every Moment Is a Moment of Learning" — Lenore Tawney. New Bauhaus and Amerindian Impulses

Nov. 14 2018

Questions about Lenore Tawney — An Interview with Kathleen Nugent Mangan, Executive Director of the Lenore Thousand. Tawney Foundation

Mar. 10 2019

kNOT a QUIPU — An Interview with Cecilia Vicuña

Aug. three 2018

Diagonal. Pointé. Carré — Goodbye Bauhaus? Otti Berger'southward Designs for Wohnbedarf AG Zurich

Feb. 12 2019

The World in the Province from the Province to the Globe — Bauhaus Ceramics in an International Context

May. 27 2019

Reading Sibyl Moholy-Nagy, Native Genius in Anonymous Compages in Northward America, 1957

Jan. 24 2019

Vernacular Compages and the Uses of the Past

January. 11 2019

The "Workshop for Popular Graphic Art" in Mexico — Bauhaus Travels to America

Oct. 19 2018

Lena Bergner — From the Bauhaus to Mexico

Oct. 19 2018

Of Art and Politics — Hannes Meyer and the Workshop of Pop Graphics

Nov. xx 2018

bauhaus imaginista — and the importance of transculturality

Kopie.jpg?w=245&h=163&c=1)

Apr. 21 2020

Mar. 27 2018

The Bauhaus and Morocco

Apr. iii 2018

École des Beaux-Arts de Casablanca (1964–1970) — Fonctions de l'Prototype et Facteurs Temporels

October. 18 2018

Les Intégrations: Faraoui and Mazières. 1966–1982 — From the Time of Art to the Time of Life

October. 18 2018

Chabâa's Concept of the "3 Equally"

Oct. 18 2018

Don't Exhale Normal: Read Souffles! — On Decolonizing Civilization

Aug. 5 2018

In the Footsteps of the Bauhaus — Its Reception and Impact on Brazilian Modernity

May. 6 2019

Ivan Serpa, Lygia Clark, and the Bauhaus in Brazil

Sep. ix 2019

Walking on a Möbius Strip — The Inside/Outside of Art in Brazil

Feb. 19 2019

The Poetry of Design — A search for multidimensional languages between Brazilian and German modernists

Jun. 8 2020

The Latent Forces of Popular Civilisation — Lina Bo Bardi's Museum of Popular Art and the School of Industrial Design and Crafts in Bahia, Brazil

Feb. 14 2019

Teko Porã — On Fine art and Life

Jun. 8 2018

Times of Rudeness — Pattern at an Impasse

Apr. 17 2019

Connecting the Dots — Sharing the Space betwixt Ethnic and Modernist Visual Spatial Languages

Dec. 17 2019

+ Add this text to your collection!

Source: https://www.bauhaus-imaginista.org/articles/5684/a-bauhaus-domesticated-in-sao-paulo

0 Response to "Max Bill Exhibition Museu De Arte De Sao Paulo in 1950"

Post a Comment